[ Home | House Rules | Jeff Dee Art Gallery | Links Page | Sitemap | V&V Cover Gallery ]

CHARISMA COUNTS

© 1985 by S. D. Anderson

"A new charisma system for the VILLAINS & VIGILANTESTM game."

A V&V Article from Dragon #100

NEWS ITEM: (Center City) The arch-criminal Killer Scumdog was foiled in his attempt to rob the Center City Orphanage today by the city's Commando Crusaders. Most of the Scumdog's henchmen were captured, but the archfiend himself escaped, and the heroes opted not to pursue him. He may be scum, but we like him, said one hero.

NEWS ITEM: (Center City) Alfred Alford, who is alleged to be the confidence man known as Mr. Charm, was walking down the streets of the downtown section yesterday morning. The good citizens of Center City reacted warily toward him; within minutes, the Commando Crusaders were on hand to beat him into submission.

Speaking from the hospital s criminal ward, police spokesman Lt. Victor Broyko said no charges could be filed against Alford, in as much as he has not committed any crimes. When asked if assault charges would be filed against the Crusaders, Lt. Broyko asked Why?

Sound ridiculous? They are, but such scenarios must happen if FGU's VILLAINS & VIGILANTESTM game is played by the rules. The higher a villain's charisma, the greater the hatred a hero has for him. This only applies to NPC reactions, but it is illogical in any event. Besides, one can find many examples of love relationships between heroes and villains in the comics. Under the existing rules, such relationships are difficult at best and impossible if both characters have charismas over 40.

The situation is even worse at the other end of the scale. Characters with low and negative charismas get positive reaction modifiers from characters on the opposite side of the law. In the case of a negative-charisma monster being encountered by a group of heroes as it ravages a city's downtown, the + 8 modifier it gets means the worst reaction possible is a 9 - neutral!

Where the existing system fails is in using the charisma score for three separate purposes. That score serves to measure the charisma of the hero, the reputation of the hero, and the charisma of the hero's secret identity - things which should be treated separately.

A superhero in his secret identity often takes on a personality different from his super-identity, to help keep his super-identity hidden. In game terms, this means that the two identities have different charisma scores. A character who is a skilled actor can usually pick the charisma score he wants each persona to have, but a typical character will only be able to modify his charisma by a limited amount. Divide a character's intelligence score by 10 and round up.

This number represents the number of points a character can credibly alter his charisma by unskilled acting ability alone. Charisma is not truly altered here; other characters have a chance of seeing through the act, and the actual charisma score should be used for saves or powers whose ranges are determined by a charisma score.

For example, David (Concussion) Havens decides to make his costumed identity appear a little antisocial and make his secret identity a little more likable to enhance his disguise. With an intelligence of 13, he can alter his charisma of 11 by 2 points. Havens would then appear to have a charisma of 13, while Concussion would be a barely tolerable 9.

Training bonuses could be used to improve the disguise, either by increasing the point spread for varying charismas or by making it more difficult for someone to see through the act. Anyone who rolls his character's intelligence score times three or less will realize that someone else is putting on an act and varying charisma. For each level of training put into this roll, lower the score the character needs to penetrate a disguise (or disguised charisma) by 5%.

In this new system, charisma and In this new system, charisma and reputation are treated as two separate but related characteristics. Charisma reflects how a character's personality directly affects other characters. Reputation reflects indirect consequences of one's actions and charisma.

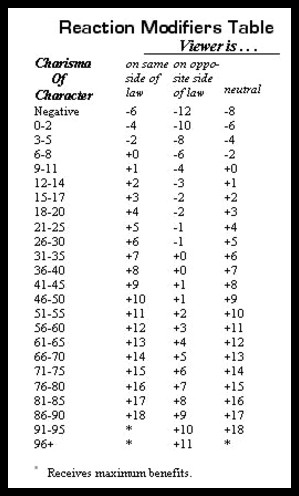

A high charisma is obviously useful, and an extremely high charisma may even make other characters forget which side of the law the charismatic character is on. Of course, an occasional psychotic might despise a highly charismatic character, and personal grudges between characters can nullify the benefits charisma usually gives. Though it makes a difference whether a character is good or evil, the new Reaction Modifiers Table given with this article does not preclude positive reactions from others as does the original system.

A good reputation canít hurt, either. In game terms, a reputation is measured by reputation (rep) points. A character's base reputation score can be calculated by the following formula: (2 x charisma score x level)/100 = rep points. To have any public recognition at all, a character must have at least 1 rep point, and any score less than one rounds down to zero. After a character acquires a reputation, fractional points can be valuable. Round any score over .5 up to the next number; if it is exactly .5, round it to the circumnearest even whole number.

There are many ways a character can acquire rep points. A referee may award or reduce them as per the rules on charisma points in section 2.9 in the VILLAINS & VIGILANTESTM rulebook; a character may acquire them through training (by cooperating with the media or hanging around criminal districts in disguise telling stories); or, outside influences can cause the character to gain or lose rep points. A local politician may decide to make the characterís existence an election issue, or a best-seIling novel about super-types may appear that prominently mentions the character.

Even characters who make no effort to build a reputation will acquire one as they progress in levels. For example, the 1st-level heroine Flame Rider has a charisma of 14 and thus a rep point score of 0.28, or 0. At 2nd level, her score would be 0.56 (still a 0). At 4th level, her score would reach 1.12 (1), and she will have a reputation. On the other hand, were she to use her first level of training to boost her rep point score by one point, she'd have 1.56 (2) rep points at 2nd level.

Characters can use rep points as charisma reaction modifiers. However, rep points do not have a specific positive or negative value assigned to them as charisma modifiers do. Charisma modifiers work in a alignment-specific manner with good, evil, and neutral categories being defined. Reputations are not that simple, and they vary greatly depending upon who is viewing the character.

For example, the hero Streetfighter has a deserved reputation for using violence to subdue criminals. To the members of the Avenue Guardians, a group of karate students who banded together to protect their neighborhoods from gang violence, Streetfighter's rep has a very positive effect. To the members of the Activists against Media Violence, Street-fighter's rep is a definite minus. Both groups are of good alignment, so alignment is not a valid indicator when figuring the effect of rep points.

In short, rep points do not measure the effect a character's reputation has on others; they only measure its magnitude. It's the referee's job to determine how a particular character's reputation is going to affect other people, assigning a positive or negative sign to the score in each instance.

While reputations will vary, certain aspects of a superhero's life are going to be fairly standard, and a few effects are going to be rather constant. A hero's (or villain's) rep should be able to counteract any unrealistic gains that his high charisma gives him. Characters on opposite sides of the law should have every opportunity to hate each others' guts, and rep points will help feed the fires.

Non-violence is a trait noticeably absent from most superbeings. Most characters are going to acquire their reputations over the course of a long career, and they are going to have to come out on top in quite a number of fights. Being tough is an inherent part of fights. Being tough is an inherent part of a supercharacter's reputation. All of the above should make people reacting to the character a little less likely to resort to violence. There will certainly be exceptions to this rule (the young punk out to make a name for himself by challenging 'old hands' comes to mind), but such exceptions should be infrequent.

How big can a reputation get? In real life, a reputation can only get so big before ceasing to be credible. In game terms, a reputation score of 10 should be the limit, no matter how high the formula says it is. Certain exceptions can be made, as close friends and arch-enemies will believe stories about a hero long after the general public shakes its collective head in disbelief.

Another thing to keep in mind is that characters may have more than one reputation, or that their reputation may vary with different people. Depending on how much bookkeeping a referee wants to do, a single character could wind up with quite a few rep scores. If your campaign is set in a modern urban area, specific reputations could be targeted at the general public, the criminal underworld, other superheroes, law enforcement agencies, the government, and covert-operations agencies.

When awarding or penalizing a character with rep points, a referee may add or subtract the points from any or all rep categories as he sees fit. Points generated through the formula should be treated as a base for all categories, since they represent the amount of reputation a character gets unintentionally. Points earned through training only alter one category, and the player must determine which category their character is going to go for first. (It's possible for a character to work out a publicity scheme that will cause the training for reputation to work simultaneously for additional categories, but it will cost Inventing points to do so.)

Other categories for classifying rep scores are possible and may even be necessary, depending on the circumstances of a referee's campaign, but too many categories will bog down the system. Limiting characters to a single reputation under any and all circumstances may not be very realistic, but it does save precious time and mental effort. If you feel comfortable with more reputation categories, by all means use them, but don't let a system designed to ease your work destroy your game.

Original Article © 1985 by S. D. Anderson. Reprinted with author's permission. HTML © 2004 - 2010 Tim Hartin.

[ Home | House Rules | Jeff Dee Art Gallery | Links Page | Sitemap | V&V Cover Gallery ]